The concept behind the $2.4 billion Alameda Corridor project isn’t altogether new.

A year ago, I wrote about the Los Angeles & San Pedro Railroad, built by Phineas Banning in 1868. It became Southern California’s first railroad, connecting Banning’s port at Wilmington to the downtown Los Angeles rail yards. Goods, including lumber and other construction materials, could now move more efficiently from the port to the burgeoning metropolis.

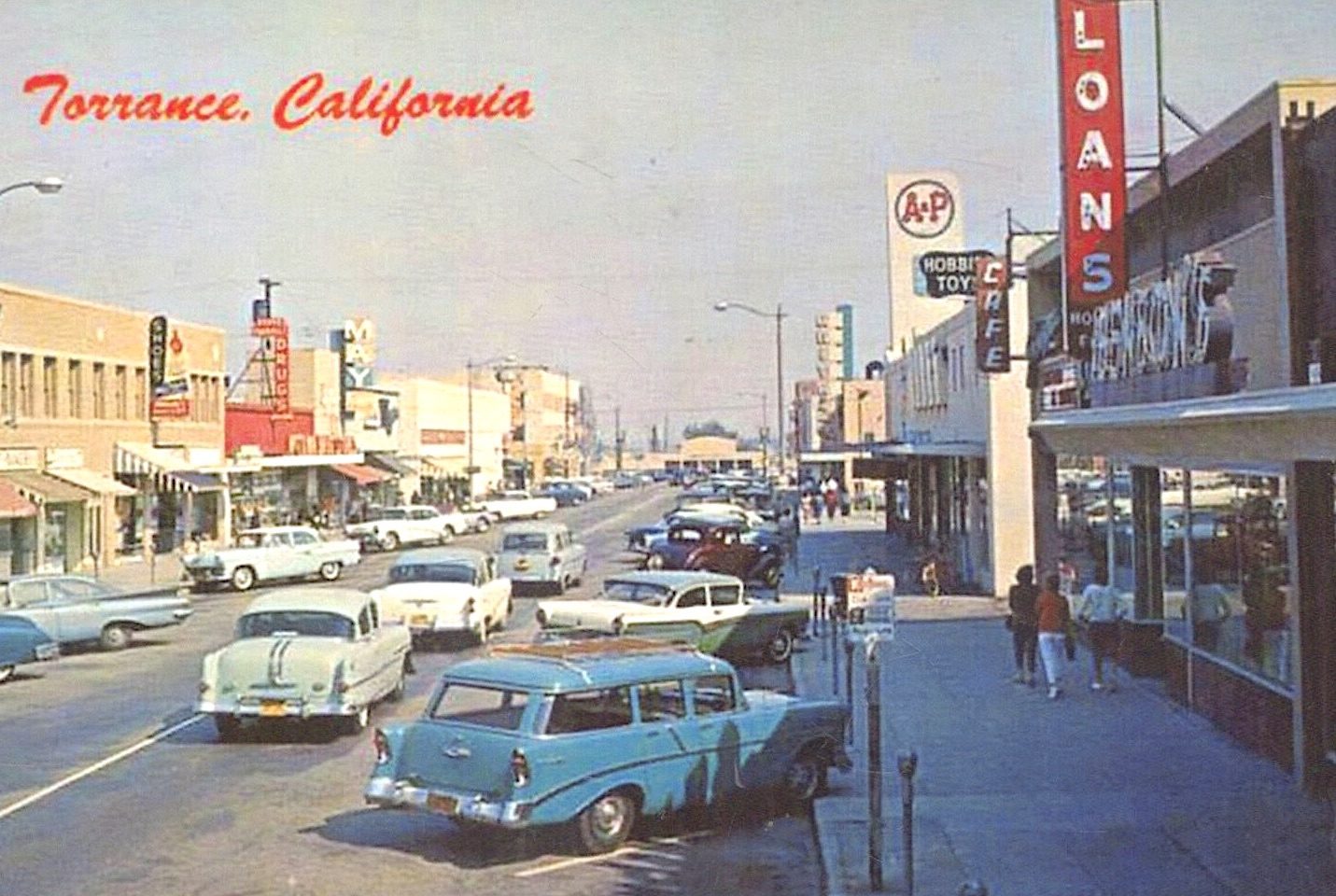

In those days, there wasn’t much civilization along the 21-mile route, but a century or so later, that all had changed. The railroad lines feeding to and from the port now passed through a densely populated thicket of cities and towns

As development along the route intensified, the railroads, now operated by Union Pacific and Burlington Northern/Santa Fe (BNSF), faced challenges.

Trains laden with intermodal containers ran along the same general route as Banning’s railroad, roughly following Alameda St. north to Los Angeles. Their progress was slowed by 209 ground-level intersections with local street traffic.

In return, the incessant parade of freight trains, some more than a mile in length, snaking their way northward to the central Hobart rail yard near Vernon caused daily traffic congestion. The slow-moving trains and idling auto engines waiting for them to cross also increased air pollution on streets all along the rail lines. The problem was especially severe in the Harbor Area.

Principals of the various government and corporate entities involved, including the railroads, cities and ports, began to take steps to find a solution in 1981, when the Southern California Association of Governments (SCAG) formed the Ports Advisory Committee to study the problem.

Its various panels and task forces began coming to the same conclusion: a central, dedicated unified rail route that would cut travel times and eliminate above-grade road crossings was a necessity. They also agreed that the Alameda route was their best option.

Such a massive undertaking would involve not only a boatload of money, but also cooperation among private and public organizations. To that end, the Alameda Corridor Transportation Authority (ACTA), was added to the alphabet soup of agencies involved in the project. It was formulated as a joint powers authority, an organizing principle that puts governing bodies from different areas together to work on large projects spanning multiple jurisdictions.

ACTA included representatives from the main players involved: railroad executives, officials from the cities along the route and representatives from the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach. Its members spent much of the 1990s obtaining various parcels of land needed, working to consolidate the various branch rail lines into one unified route, planning and designing that route, and attempting to obtain funding for the massive undertaking.

In addition to multiple bridges and underpasses bypassing street traffic routes, the Alameda Corridor plans also included an unusual 10-mile stretch known as the Mid-Corridor Trench. The below-street-level passage is 33 feet deep and 51 feet wide and stretches from the 91 Freeway in Compton north to 25th St. in Los Angeles.

The entire project, originally given a $2 billion price tag, ended up costing $2.4 billion. Sources of its funding included the two ports, ACTA, the U.S. Dept. of Transportation, the Metropolitan Transit Authority and various other state and federal funds.

Construction on the project began in 1995. The first completed structure, the 470-foot Carson St. rail overpass in the city of Carson, opened that December and cost $13 million.

With all funding finally secured, including a $400 million Dept. of Transportation loan authorized by President Bill Clinton in January 1997, construction began in full force in 1998.

Unlike many such massive transportation projects such as the 105 Freeway and the first installment of Los Angeles’ light rail line, the Alameda Corridor came in on time and under budget when it officially opened on April 12, 2002.

The final piece of the puzzle, a $107 million half-mile-long bridge carrying Pacific Coast Highway traffic over the train route, opened on March 4, 2004. It was authorized a year after the original project was finished.

After the Alameda Corridor opened, trains from the ports were able to travel up to Los Angeles unimpeded at a speed of 40 mph, instead of their previous 8-15 mph speeds and frequent slowdowns and stops. Street traffic flow also improved greatly once the train crossings vanished.

Though it was a rousing success, the Alameda Corridor project hasn’t solved all the port area’s transportation problems. It has greatly improved the movement of longer-distance freight container traffic, but it turns out that semi trucks are cheaper and more efficient for transporting goods locally.

Truck traffic continued to grow after the Corridor opened, taking its toll on the 710 Freeway, which now needs not only repairs but also a costly major renovation.

As a result of the trucking increase, the Corridor’s train traffic hasn’t risen as much as predicted. As a result, it has faced financial stresses during slower periods, as it relies on usage fees from the train companies to pay back the debts from its construction.

In 1998, work on the Alameda Corridor East project began, with the goal of extending the Corridor east from downtown through the San Gabriel Valley. As of 2023, more than half of its targeted gate crossings had been eliminated, with construction still ongoing.

In June 2024, matters regarding the Corridor fell to District 15 Los Angeles City Councilmember Tim McOsker, who was elected chair of the Governing Board of ACTA for the 2024-25 term.

Sources:

Alameda Corridor Transportation Authority (ACTA) website.

Daily Breeze archives.

Los Angeles Times archives.

Union Pacific website.

Wikipedia.